The Improbable Legacy of Napoleon Bonaparte’s Nephew

Louis-Lucien Bonaparte was born in 1813 in Worcester where his father, a brother of Napoleon, had been imprisoned following his capture by the Royal Navy while on his way to America after falling-out with his powerful brother. At the age of one, his parents returned to their Italian estate where Lucien grew up. He studied chemistry and mineralogy in Italy before serving in various elected positions with the French government. Louis-Lucien was awarded the title of ‘Prince’ by his cousin and thus became a member of the French aristocracy under the Second French Empire. In the early 1850s, at the end of France’s Second Republic, he returned to England where he took up residence in London and became immersed in his love of modern languages; researching and publishing books and guides on European languages and dialects at his own expense.

“Scholastic interest in (dialects) grew throughout the 19th century prompted by the academic advances in the study of Old English and consequent realisation of the ancient pedigree of much dialect vocabulary. … The intention was presumably to show how sonorous and effective the varieties of local dialect could be as spoken – and literary? – languages.”

Bill Griffiths

North East Dialect: The Texts, Centre for Northern Studies, University of Northumberland, 2000.

Prince Louis-Lucien Bonaparte was an accomplished linguist who was extremely knowledgeable in just about every European language as well as many of the dialects, particularly in the Basque language in which he was a recognized expert. He was extremely well-connected counting Gladstone as a friend and occasionally dining with Queen Victoria at her Windsor residence. Although Louis-Lucien’s private income started to dry-up after the fall of the Second Empire, in 1883 he was granted a civil list pension for his work on English dialects. He died in Fano, Italy in 1915 and was buried in St Mary’s cemetery in Kensal Green, London.

His dialect studies draw upon both written texts and the results of field work, which consisted of the direct interrogation of native speakers. The written versions were generally produced by collaborators who had been expressly instructed to record only those forms that were contemporary, not deliberate archaisms and those that were native to their region.

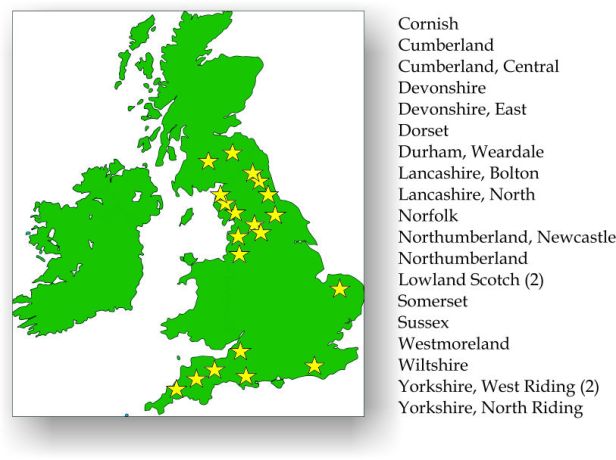

In 1862 he published a compilation of 24 dialectal translations of the Old Testament passage, The Song of Solomon, which he commissioned from local dialectologists from throughout England and southern Scotland.

According to a register of his known works, six Biblical translations were commissioned in the Northumbrian dialects, four of which appear in The Song of Solomon:

The Song of Solomon in the Durham Dialect as Spoken at St. John’s Chapel by Thomas Moore, 1859

The Song of Solomon in the Northumbrian Dialect by Joseph Philip Robson

The Song of Solomon in the Newcastle Dialect by John George Foster, 1858

The Song of Solomon in the Newcastle Dialect by Joseph Philip Robson, 1859

Two other translations are also noted in the register:

The Book of Ruth in the Northumberland Dialect by J. P. Robson, 1860

The Song of Solomon from the English Translation into the Dialect of the Colliers of Northumberland but Particularly Those Dwelling on the Banks of the Tyne by J. P. Robson, 1860.

The translations were featured in the play, Geordie: The Musical, written by Jarrow playwright Tom Kelly and originally performed at the Customs House Theatre in South Shields. In the scene below, an enthusiastic Tommy Armstrong, (Micky Cochrane) responds to Oxford student, John Thompson (Adam Donaldson), and translates The Song of Solomon into three Northumbrian dialects. The audience shows its delight as Tommy Armstrong easily slips between dialects.

Excerpts from the Song of Solomon in Northumbrian Dialects:

Weardale Dialect

2.8 T’voice uv me beloved! Behowld, he cumeth lowpin attoppa t’moontens, skippin atoppa t’hills.

2.9 Me beluved’s leyke a roe er a young hart: behowld, he stands ahint our wo, he lewks furth at t’windows, showen hissel through t’lattice.

Newcastle Dialect

2.8 The voice o’maw beluived! seesta’, he comes lowpin’ upon the moontins, skippin ower the hills.

2.9 Maw beluived is like a roe or a young hart: seesta’, he stan’s ahint wor wa’, he luiks oot at the windis, showin’ his-sel thro the lattis.

Northumbrian Dialect

2.8 Wheest! It’s the voice o’maw luve! Leuk! Thunder he cums lowpin’ upon the moontins, an skurryin ower the hills.

2.9 Maw troo-luve’s like a buck or a leish deer: assa! he’s stannin ahint wor wa’; he’s leukin’ oot o’ the windors, an showing’ hissel’ thro’ the panes.

St James’ Bible

2.8 The voice of my beloved! Behold, he cometh leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the hills.

2.9 My beloved is like a roe or a young hart: behold, he standeth behind our wall, he looketh forth at the windows, showing himself through the lattice.

References:

Out of The Confusion of Tongues: Louis-Lucien Bonaparte (1813-1891). British Library.

The Song of Solomon in Twenty-Four English Dialects: compiled by Prince Louis-Lucien Bonaparte, 1862

Several of these publications, including the Song of Solomon in Twenty-Four English Dialects, can be viewed on Google Play Books.